The beverage ‘sake’ in English is called nihonshu and is produced in Japan with Japanese rice. Seishu is also refined sake, but can be produced anywhere in the world. Sake in Japanese actually refers to any and all alcoholic drinks. Therefore, when you’re travelling in Japan and want to try Japanese sake, you have to ask for nihonshu, or you will get a beer/cocktail/wine list.

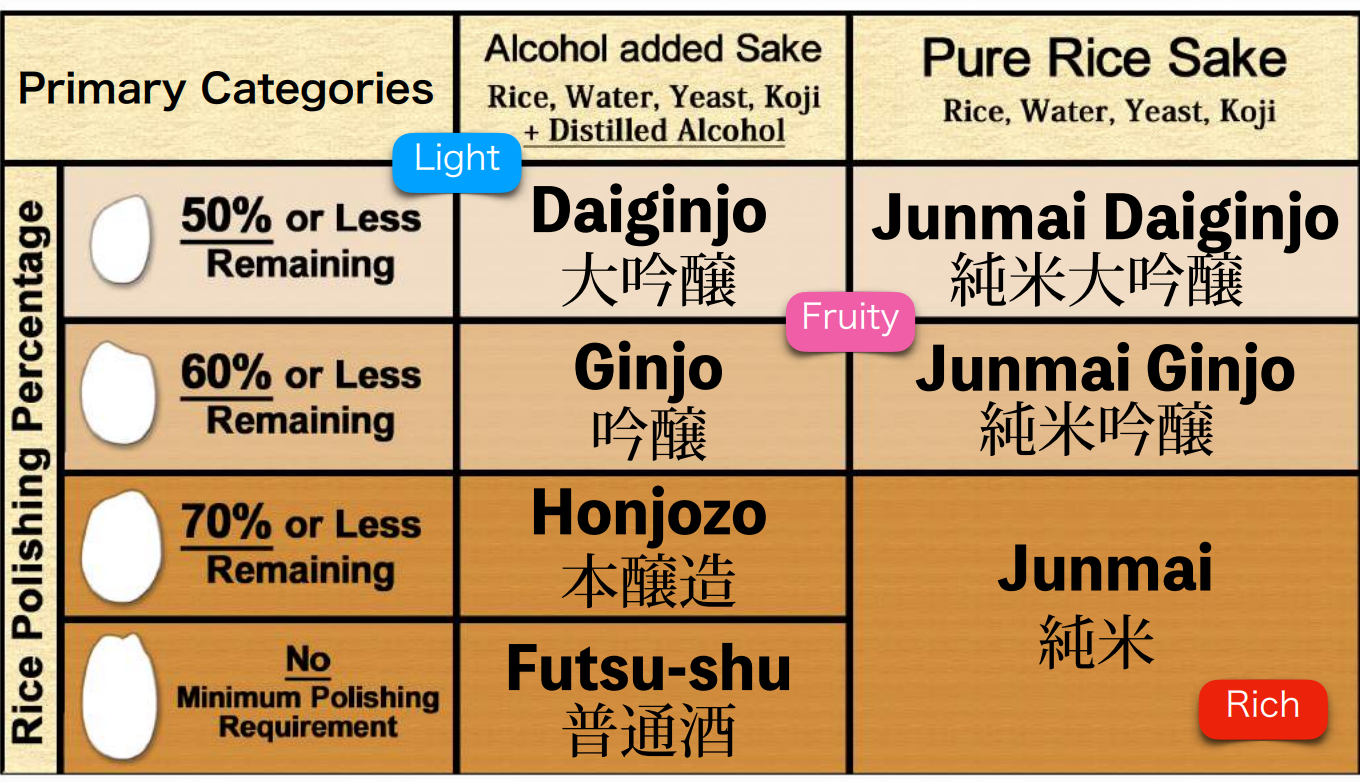

There are many different grades of sake that are designated based on the brewing process and type of rice used. Nihonshu can be divided into primary categories based on rice polishing percentage. Sake rice is different from the rice you cook for meals, and can be polished to different levels to achieve different tastes.

(Junmai) Daiginjo- 60% or less remaining

Junmai- 70% or less remaining, no minimum milling requirement

Honjozo- 70% or less remaining

Futsu-shu- no minimum milling requirement

Pure rice sake is called junmai (純米), but you will often find sake that was made with additional distilled alcohol, those will not have ‘junmai’ in the name- like Ginjo or Daiginjo. They tend to have a lighter rice flavor.

There are a few ways we can predict the flavors of nihonshu by reading the bottle. Of course, everyone tastes Japanese sake differently and you aren’t exactly guaranteed a flavor until you taste it for yourself. Ginjo fermentation leads to a fruity aroma and flavor profile, which is one of the most distinguishable traits between sake categories.

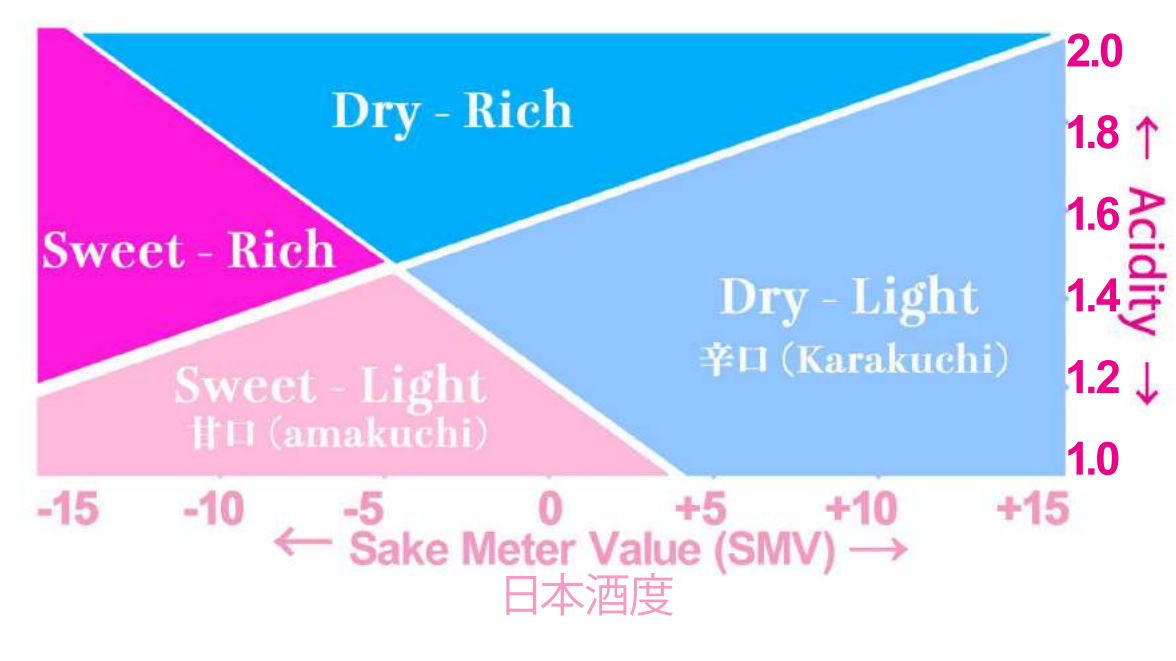

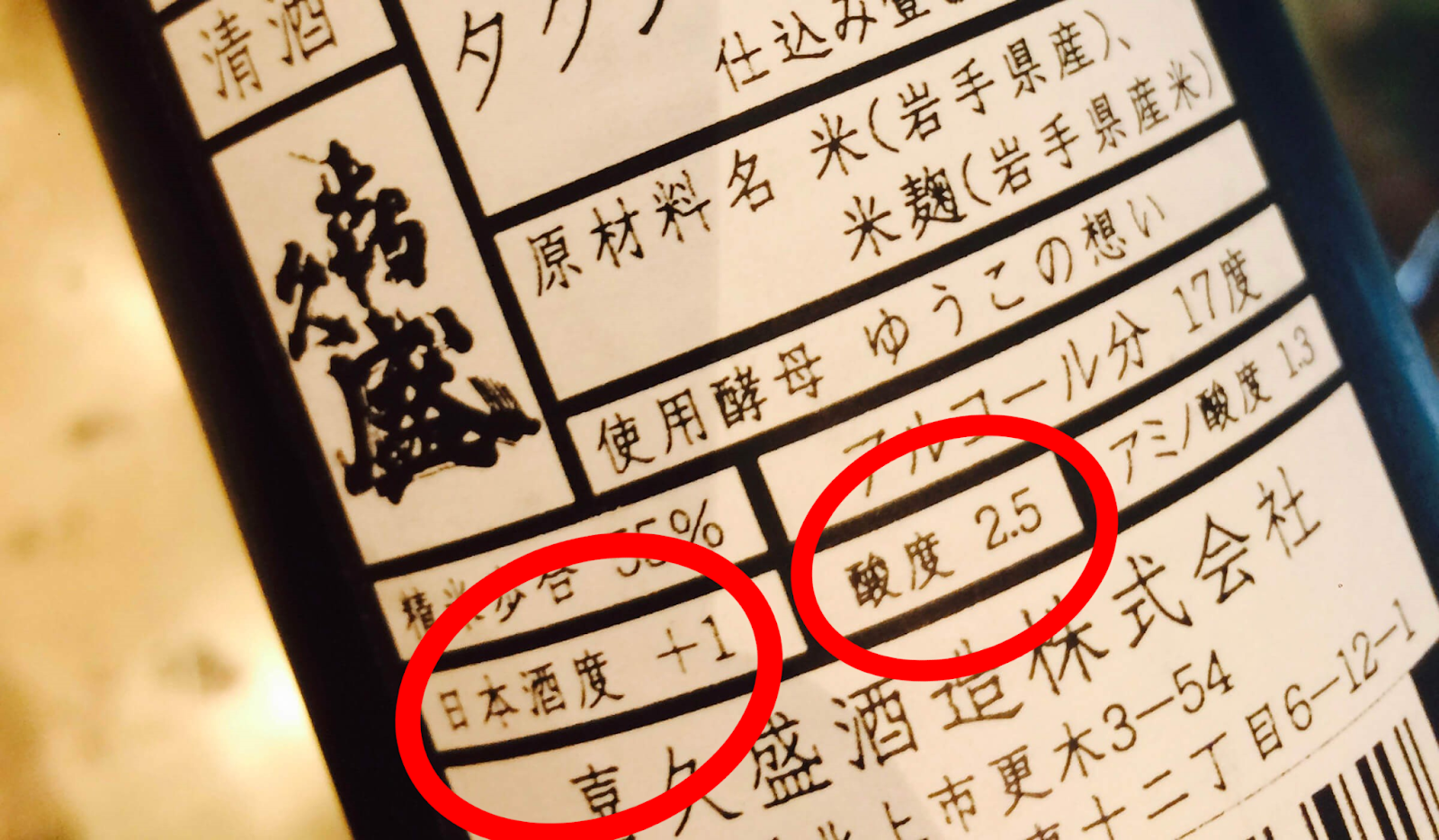

You can guess the taste by reading the acidity (酸度, sando) and sake meter value (日本酒度, nihonshudo). Here is another chart to help you understand the profiles:

For example, I like dry, light sake. So I tend to go for a Junmai Daiginjo. My father likes bourbon and whiskey, so he tends to go for a Junmai.

Of course, there are other categories not shown in the primary category chart that I shared with you. Here’s a short description of those:

Nigorizake (濁り酒)- unfiltered sake, coudy, textured, fizzy on the tongue

Namagenshu (生原酒)- raw sake, non-diluted

Koshu (古酒)- aged at least 2 years, usually very strong

Tokubetsu Junmai (特別純米)- at least 60% polished, special brewing process

If you’ve had traditional Japanese-style meals, you might notice that they are often served as multiple items in smaller quantities, usually paired with white rice. At various tasting experiences, I learned that Japanese people often combine different flavors in their mouths as they eat. This is the same theory used to pair foods with sake. The easiest theories to remember are:

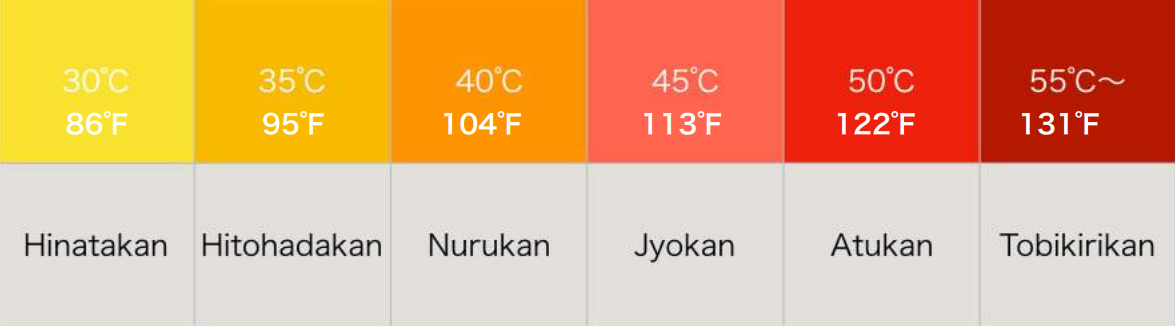

Most bottles of sake come with recommended temperatures for drinking on the bottle. You can also request sake temperatures at a sake bar using this general guide:

The sake that’s recommended to be enjoyed both cold and heated include junmai, futsu-shu, and honjozo due to their rich and un-fruity flavor profiles.

I recommend omiyage (souvenir) stores! They usually have a wide selection of local sake and many different kinds of unique or special edition bottles. You can also find sake specialty shops in most places in Japan, I definitely recommend those for local flavors over grocery store or conbini sake.

Hanzo (Hikone, Shiga)

Bar Kuon (Hikone, Shiga)

Asano Nihon Shuten Kyoto (Kyoto)

Kyoto Insider Sake Experience (Kyoto)

Traditional Kyoto Kaiseki Meal and Local Sake Tasting (Kyoto)

Hit the Town with a Sake Sommelier (Tokyo)

Taste Craft Sake and Discover the Many Varieties (Tokyo)